Email Me beckyvena@gmail.com

27 MAY 2017

METACOGNITION AND THE MUSIC MIND

They call your name, the crowd claps as you walk through the stage doors, the lights are shining. You reach the piano, sit down, pause and take a shaky breath. Your hands are on the keys now, the instrument is illuminated, the crowd, silent. The first note is the hardest.

If you are a music student, you probably know this feeling: performance anxiety. But performances are not the only source of stress in the field. One musician knows as well as the next the perfectionism involved in learning an instrument, the mass amounts of homework for both music and general education classes, and the countless hours of practice that go into a music degree. Any subject can be difficult, but the stresses involved in a music degree may be different. Last year I conducted a study that looked into these unique stresses, and specifically how they can lead to music student burnout.

Burnout is a state of physical, mental, or emotional exhaustion caused by prolonged stress or overwork. It can lead students to experience feelings of depression, anxiety, depersonalization, and lack of accomplishment. For music students, it can mean putting down an instrument you’ve played for your entire life and never picking it up again.

Feeling the stresses of a music degree myself last year, I wanted to find ways to combat burnout, or, better yet, prevent it altogether. I surveyed music students at the University of Denver, I interviewed one, and I tested some of my hypotheses on myself, and culminated it all into a research essay .

In my research, I found that there are already numerous methods to help students cope with burnout. These include:

-

Getting more and better sleep

-

Eating the right amounts and the right foods

-

Exercising regularly

-

Setting more reasonable goals

-

Becoming involved in extracurricular activities

-

Spending time socializing and/or in a supportive environment

-

Seeking professional help or medical treatment

But if you’re a music student, you know that you may not have the time, resources, or even the control over your own schedule to be able to do these things. Knowing you are stressed beyond reason and only finding a list of cliché phrases to help “cure” you will just make your frustration worse.

So what do you do? My research and experience in a writing class led me to something I had not considered; though looking back, it seems so simple. The key is not to attempt to change external factors that you may or may not have control over. The key is to change how you think about practice. The key is metacognition.

Metacognition can most simply be described as the act of thinking about thinking. It involves understanding why you choose a certain course of action rather than simply choosing that action without thinking (even if you chose correctly).

In a survey I conducted as part of my studies, over 50% of students stated that they became frustrated while practicing their instrument because they did not know how to effectively improve. This is where metacognition comes in. A good performance is one thing, but if you don’t know specifically what it is that made your performance good, how will you ever replicate it? Good and truly effective practice comes from knowing exactly and specifically what you need to do to improve your playing. It is not enough to know that a certain passage you’re playing “just doesn’t sound quite right”. You need to know what about it is causing it to sound off. And this requires the use of metacognition.

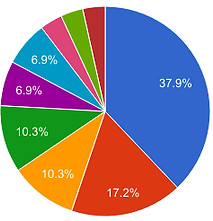

What do you feel causes any frustration you feel with your practice?

Learning too slowly / Not making progress fast enough

Not knowing how to improve

Physical health problems

Difficulty

Lack of focus

Practice isn't fun

Not retaining info

Letting people down because I'm not good enough

Poor sightreading skills

55.1% of students stated they became frustrated while practicing their instrument because they felt they were learning too slowly / not making enough progress fast enough, or they didn’t know how to improve; but these could all be considered essentially the same source of frustration: not knowing how to improve.

Luckily, metacognition is a skill that improves with practice. Here are some ways to develop it:

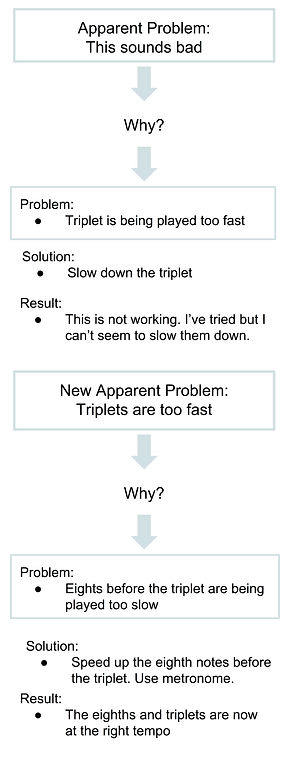

CONTINUALLY ASK WHY

To start, if you are presented with a problem, try continually asking yourself “why?”. For example, you may notice that a measure you’re playing just sounds off. Asking “why?” may lead you to the conclusion that you are playing a certain series of notes too quickly. But after trying to slow them down, you can’t. Instead of getting frustrated and giving up, ask yourself why again. Suddenly you realize that you are actually playing the notes too quickly because you’re playing the notes before them too slowly, and so your mind is trying to compensate to stay in time.

Asking yourself “why” until you get to the real root of the problem is essential in order to actually solve the problem and not just cover up its symptoms. If you can find the root of the problem, then you can figure out how to fix the problem.

ACCESS HIGHER METACOGNITIVE SKILLS

Possibly one of the best ways to improve metacognition besides constantly practicing it is to have access to metacognitive skills beyond your own. Your professor is the obvious person to go to for help with this.

Though it seems counterintuitive, having lessons more frequently could actually help improve your practice and your learning. For example, what if you had two lessons a week instead of only one? Yes, you would have less time in between lessons to accomplish tasks, but you would have twice the exposure to your professor’s abilities. Your professor could more quickly catch any issues with your practice and get to the root of the problem before it becomes too hard to fix. As your metacognitive skills develop, your practices will become more and more effective. You may have less time in between lessons to accomplish goals, but your practices could become so efficient that you could get the same amount of tasks, if not more, accomplished as you would with only one lesson per week. This increase in effectiveness and efficiency will help you really see the progress you’re making. This sense of accomplishment can go a long way in diminishing feelings of stress, even if the workload stays the same.

PRACTICE, PRACTICE, PRACTICE

Another approach to improving metacognition is to actively analyze performances. This could be done in both a group and an individual setting. Begin by listening to a performance on your instrument. Practice deciding what was done correctly or incorrectly. If you liked a section, ask yourself why. Was it the use of the pedal? Did the performer play the dynamics a certain way that surprised you? And if you didn’t like a section, why not? Perhaps there weren’t enough dynamics? Maybe they held a single note too long for your taste, or put the emphasis on the wrong note? Imagine yourself playing the piece, and what physical things you would do the same as or differently than this performer.

In the end, metacognition is all about specificity. If you cannot identify specific problems with specific solutions, you will only be able to improve so far. In your practices, try to identify one very specific problem at a time. Ask yourself why that problem exists. Then ask yourself what you need to physically change in order to fix the problem. Are you holding your hands wrong? Do you have the wrong posture? What can you do differently to achieve the sound you want? It turns out the solutions to large problems lie in fixing one tiny detail at a time.

Have you or someone you know experienced burnout? What helped you? What advice do you have to music students, or college students in general? Comment below!